The Libyan crisis constituted a multi-dimensional international phenomenon, as its repercussions were not limited to political turmoil, but rather became an international dilemma as a result of illegal immigration towards Europe.

Several geographical factors played a role in making Libya a major transit country for African migrants towards Europe, such as its proximity to European shores, its sharing of long land borders with six countries: Egypt, Sudan, Niger, Chad, Algeria, and Tunisia, and the length of its coast on the Mediterranean Sea (1,770 km). Making it a major departure point for illegal immigrants trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe, and after the collapse of the political regime of President Muammar Gaddafi, this phenomenon escalated and became a lucrative trade for militias and smuggling networks.

Shocking statistics:

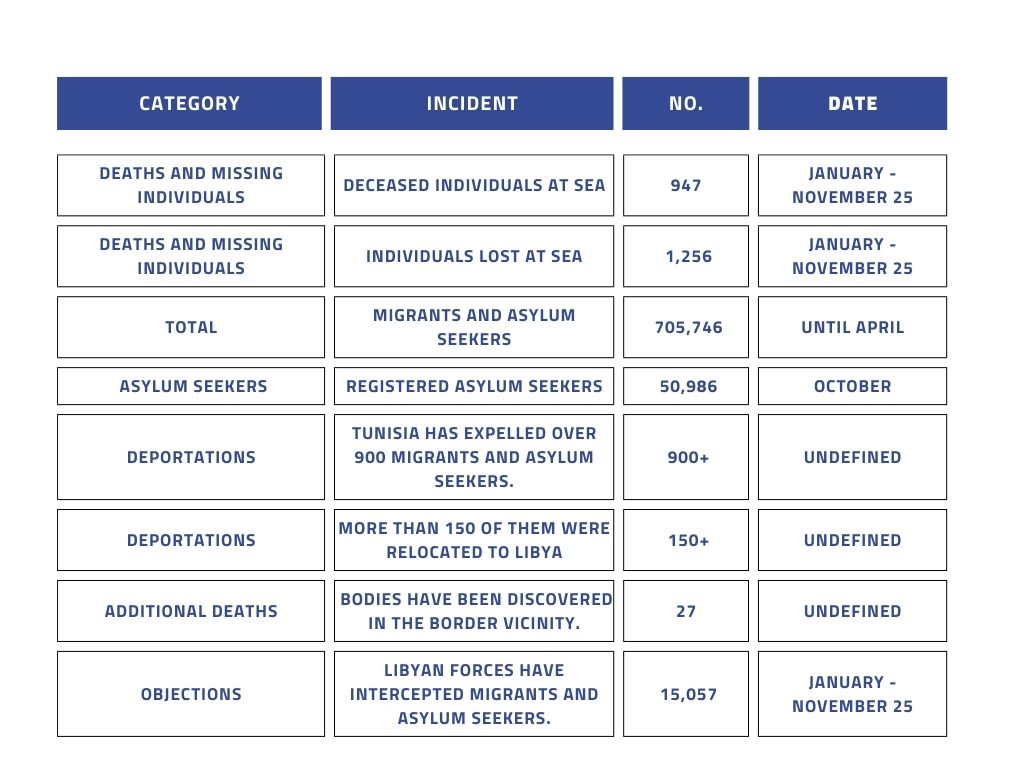

The numbers show that the issue of migrants has clearly worsened over the past year, as the International Organization for Migration counted the deaths of 947 people and the loss of 1,256 others at sea on the migration route after leaving Libya between January 1 and November 25.

1

705,746 migrants were counted in April, while the number of asylum seekers in October reached 50,986. The statistics also show that Tunisian security forces expelled more than 900 African migrants and asylum seekers to a remote military buffer zone on the Tunisian-Libyan border, and more than 150 people were transferred to Libya. . According to the Libyan authorities, at least 27 bodies have been found in the border area since the start of the expulsions.

Libyan forces also intercepted 15,057 migrants and asylum seekers who were trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea and returned them to Libya during the year 2023, according to statistics from the international organization, where they faced arbitrary detention in inhumane conditions in facilities run by the Ministry of Interior of the government of Abdul Hamid Al-Dbeibeh, in addition to being detained by smugglers and traffickers. Human beings, where they were subjected to forced labor, torture and ill-treatment, extortion, and sexual assaults, according to the fact-finding mission.

Migration and the political transformations

Before 2011, the Libyan government had relatively control over the migration movement through the country, and used this issue as a means of putting pressure on Europe, by opening or closing the “exit valve” depending on the state of relations with European countries.

There was a treaty between Libya and Italy under which the latter pledged to provide five billion dollars to monitor immigration, which contributed to significantly reducing the flow of migrants, but the collapse of institutions after the fall of President Muammar Gaddafi created a security vacuum that led to the flourishing of the human smuggling trade, as militias and armed groups benefited from the absence of the state. Lack of border controls.

Smuggling networks took advantage of the political and security chaos and transported migrants from the southern border, across the desert and remote areas, to the northern coast, where they were loaded onto boats heading to Europe.

Reports indicate that armed groups in Libya benefit financially from these activities, which further complicates the security situation in the country, at a time when the migration circle has expanded after the unrest in the Middle East and North Africa.

Migration is no longer limited to flows coming from Africa, but rather increased with the escalation of conflicts in Syria and Palestine, and political chaos created a magnet for migrants fleeing wars and conflicts in their countries, but African nationalities remained the highest, according to the International Organization for Migration.

The five largest nationalities of migrants in Libya are from Niger (25%), Egypt (24%), and Sudan (18%). Estimates indicate that more than 600,000 migrants belonging to more than 44 nationalities are currently in Libya.

A political crisis par excellence

Reading the data provided by the International Organization for Migration makes it clear that illegal immigration in Libya is primarily an African political crisis. The unrest and armed conflicts within the African belt from Sudan all the way to Mali constitute the depth of the migration crisis, while Libya appears to be within the scope of providing logistical support to the smuggling networks that “endemic” as a result of the political turmoil of 2011, and two fundamental issues can be noted in addressing this issue:

- The first is to focus on joint treatment with European Union countries in operations to pursue smuggling within the Mediterranean waters. International cooperation has practically created a front between the south and north of the Mediterranean, and attempts have been made to combat migration at the end line in Europe, while it is supposed to start from deep within Africa.

Certainly, the European Union does not seem concerned with the lines of illegal immigration at their starting point, as it views armed conflicts within a general international framework, but the issue seems more complex than the point of arrival of the immigrant to Europe.

The active migration movement is the result of political accumulation and not only the result of armed conflicts that exacerbate the situation. Migration began as a result of the “impoverishment” of the African continent a long time ago, in which European countries were the largest player.

- The second is directly related to the Libyan situation, as immigration issues are used to shed light on the Libyan political crisis, and to create points of contact for various security interests with Libyan parties that are mostly outside any Libyan political legitimacy.

The humanitarian dimensions of illegal migration through Libya represent the last picture of an African political history created primarily by the interests and investments of European companies. The complex problem of this phenomenon begins and ends with Western policies, and with the ability of African alliances and organizations to draw up new policies that not only limit conflicts, but also design different development strategies. qualitatively different from the previous one and far from the major investments of international companies.

Written by Nidal Al-Khedary

The head of the Amazigh in Libya..Closing the Ras Jedir crossing may ignite war