The Italian colonization of Libya was not just an event in the history of Africa’s largest oil state, and one of the most important countries on the North African map, but part of a past that Libyans are still suffering from and struggling to get rid of.

The Libyan present is haunted by all the events of the beginning of the twentieth century, and with a memory saturated with images of occupation, tyranny, and exile that Libya witnessed in the colonial era, which Rome is trying to exploit with all its tools.

Italian politics goes too far in this area, evoking the era of the Libyan-born Roman emperor Septimius Severus, who was a symbol that was exploited during Italy’s modern struggle to build its colonies.

A turbulent historical scene

Italian calls in the early twentieth century used historical figures such as Severus to legitimize their colonial ambitions, and evoking the past was a way to rally support among Italians, as the colonization of Libya was a matter of dispute, which prompted intellectuals and poets to lead the campaign to promote the Italian invasion of Libyan territory, and Gabriele Danunzio’s poems represented this trend as he restored with his poetry the glory of Rome’s historical relations with the region.

Italian ambitions collided with the Libyan resistance, which together with Turkish forces constituted an obstacle, and turned the Italian invasion from a quick military maneuver into a long-term conflict, especially with the start of World War I, which saw the intensification of Libyan resistance and the Italian forces suffered repeated defeats, but the arrival of the fascists to power later, changed the tactics of the invasion into an all-out war, including the establishment of concentration camps and a scorched-earth policy.

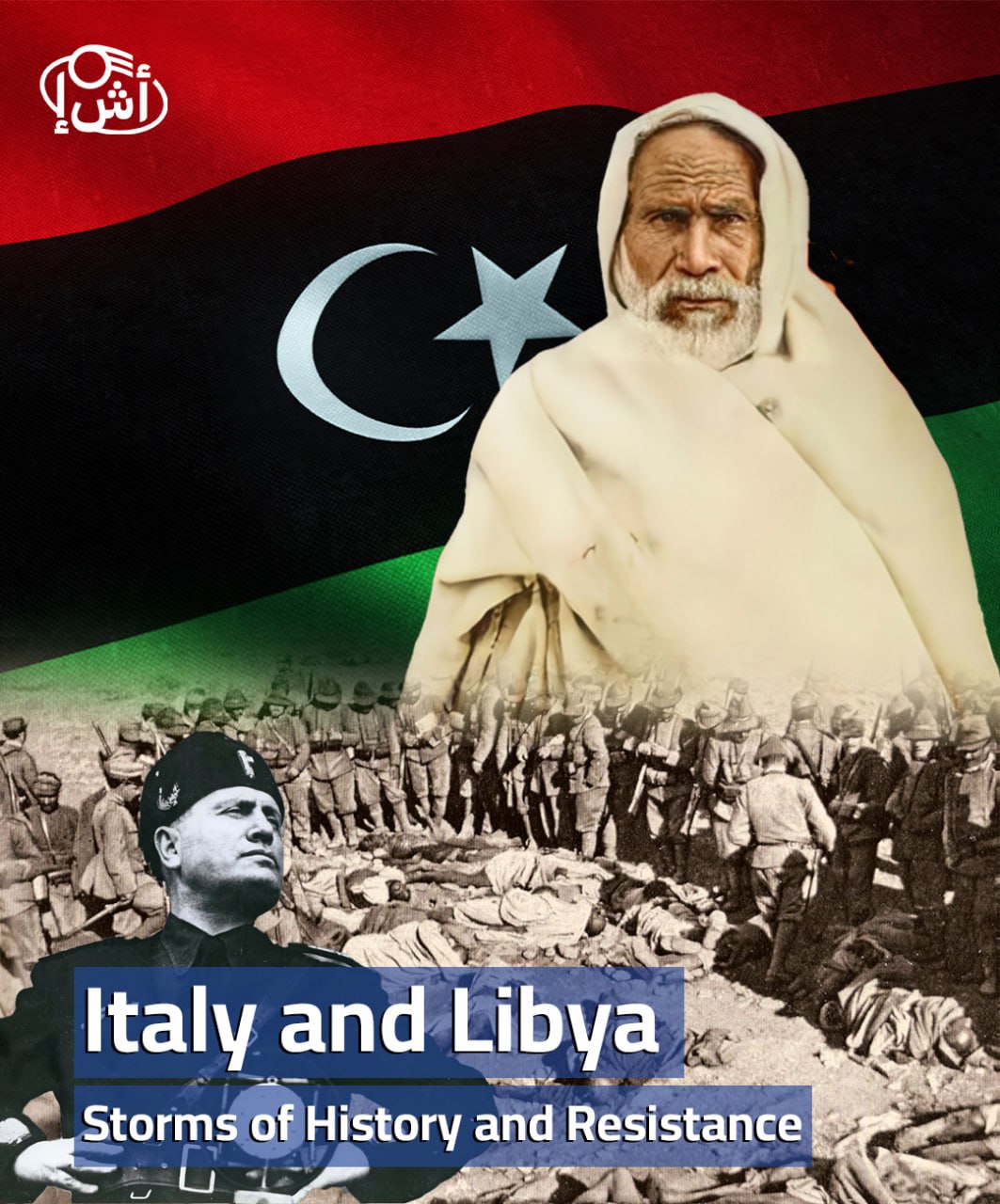

Despite this brutal campaign, the Libyan resistance, led by figures such as Omar al-Mukhtar, continued until Italy’s eventual defeat in World War II prompted a reassessment of the Italian colonial project.

The Long Journey of Resistance

The Italian discourse on the occupation of Libya talked about civilization and liberation from Ottoman neglect, but the event broke the pretexts initiated by the Italian General Carlo Caneva, the governor of Tripoli from October 1911 to September 1912, with his statements about peace, but he proceeded to commit the massacre of Manshia Square in Tripoli, in which thousands were massacred, from children to the elderly, which ignited resistance from the heart of the culture of Libyan society manifested in the Senussi way.

Senussi, this Sufi movement formed part of the social and political fabric of Libyan society and was led at that stage by Ahmed Sharif Al-Senussi, and the group went beyond its religious foundations to become a beacon of national liberation by mobilizing city dwellers, tribal leaders and common people, and the Libyan Senussi movement turned into a large front against the Italian incursion.

In practice, the Italian aggression led to the unification of the disparate Libyan tribes and regions, and formed a common identity through resistance, and prominent leaders emerged who were able to gather Libyans to defend the territory, including Omar al-Mukhtar, whose name became synonymous with Libyan steadfastness.

The Libyan resistance was marked by fierce battles against militarily superior Italian forces with a sense of racial superiority, and the Libyans used guerrilla tactics and intimate knowledge of the terrain in their war against the Italian colonizer.

The resistance paid a heavy price in its defense of the Libyan land, and the memory of the Libyans still carries pictures, and the resistance was not without its martyrs whose sacrifices gave the struggle a sacred aura, according to estimates, the number of Libyan battle martyrs in the first phase reached 33.181 martyrs.

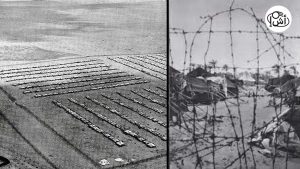

The other side of the Libyan suffering appeared in the 37,763 detainees, most of them from the Green Mountain, where the majority of these detainees died inside the mass detention centers surrounded by barbed wire and mines, and those who did not die of hunger and cold were harvested by the minefields planted around those prisons that continue to claim the lives of Libyans until today.

In contrast, the Italians forced a number of Libyans to fight in the ranks of its forces in Eritrea, Abyssinia and Somalia, and historical sources estimate that Italy recruited 25,738 Libyan citizens in World War II against the Allied forces.

The path of Italian colonialism

Italy, especially under the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini, intensified its efforts to oppress the Libyan people, and policies of repression were used, including the establishment of concentration camps and the implementation of mass punishment campaigns, the most famous of which was in the village of Al-Aqila, west of Benghazi, about 280 kilometers, where it became a mass concentration camp in which two-thirds of those who entered the prison died since its establishment in 1928 until 1931.

According to some statistics, the number of detainees reached half a million people, of whom at least 130,000 were killed, while four main detention camps were documented: Al-Egaila, Marsa Al-Brega, Sayed Ahmed Al-Maghroun in Al-Mejren, and Salouk.

The effects of Italian colonialism on Libya remained for decades, and not only drew the memory of society, but also drew the colors of politics, whether in the current form of Libya or even in the forms of political and tribal distribution throughout the country, Italy’s relinquishment of its control was not just a withdrawal only because in the end it established a relationship that can be observed until today, especially in Libya’s policy to build its state over the past decades, whether in the monarchical phase or during the period of the “Libyan Jamahiriya”, or even in the current stage of turmoil.

Written by Mazen Bilal

The Tripoli Criminal Court issues prison sentences for three defendants in immigration cases