The Endowments Authority of the outgoing National Unity Government in the Libyan capital, Tripoli, issued a fatwa implicitly disbelieving the followers of the Ibadi sect, which is embraced by most of the Amazigh component in the country.

The fatwa issued by the Endowments Authority in Tripoli sparked a widespread religious controversy, the first of its kind since the end of ISIS and the cessation of takfiri fatwas that caused the loss of thousands of lives between 2013 and 2018.

The fatwa coincided with the tension in the relationship between the government of Abdul Hamid Al-Dbeibeh and the Amazigh of western Libya due to the dispute over assuming control of the Ras Jedir border crossing, which prompted many parties to describe this fatwa as “political,” and could open the door to major persecution of the Amazigh component under religious pretexts.

The successive events regarding the Amazigh constitute a new scene for the Libyan situation, as they create tensions that complicate the horizon for a solution and increase the sectarian quarrels that Libya has witnessed in recent years. Although the fatwas issued recently regarding the Amazigh have not been given an official status by the government in western Libya, they are at the same time. Time has opened a political door to contradictions within society, and this matter is reflected at the general level, making political agreements more difficult and increasing military quarrels, especially in areas where the Amazigh are present.

Basic wallpapers:

The Berbers are considered, according to contemporary classification, to be among the indigenous peoples of North Africa. Their history in Libya extends back thousands of years. They are concentrated in Libya mainly in mountainous areas such as Mount Nafusa, and in coastal cities such as Zuwara. They also live in other regions such as southern Libya and in some urban areas. Such as Tripoli and Benghazi , They speak their mother tongue, Amazigh, which consists of several different dialects.

Estimates indicate that the percentage of Amazigh in Libya ranges between 5% and 10% of the population, and they faced political and cultural marginalization in Libya, especially during the period of Gaddafi’s rule, which took an Arab direction at the national level.

In the interim constitution of 2011, the Amazigh language was recognized as part of the Libyan cultural heritage, and they share with the rest of the Amazigh of North Africa that they speak languages belonging to the Amazigh family, a group of local dialects that includes Tashalhit in Morocco, Kabylie in Algeria, and Shawia in Algeria and Tunisia. , along with the Amazigh language in Libya.

At the regional level, there is a group of bodies such as the World Amazigh Congress (CMA), which was founded in 1995, the Amazigh Association, which operates at the level of the Maghreb and includes many local branches in countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, and the Movement for Autonomy of Mzab In Algeria, which works to strengthen the rights of the Amazigh, especially the Mozabite community.

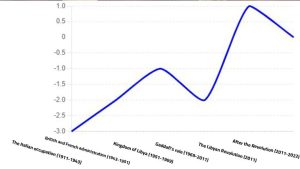

An illustration of the Amazigh reality during different stages

New disagreements

During the era of President Muammar Gaddafi, the Amazigh problem was qualitatively different, as it was not linked to a sectarian or religious situation, and the contradiction was primarily cultural, with Gaddafi following an Arab trend that made it difficult for the Amazigh component to use its cultural heritage in public life, but this problem did not appear on the surface of life. Politics is a result of the centralization of the state, and the marginalization of the Amazigh did not cause tensions at the level of Libyan politics, as they lived within the general Libyan situation in all its details. The state’s fanaticism was imposed on everyone without special discrimination, while the contradictions today constitute a special phenomenon. It does not try to impose a special culture on the Amazigh, but rather threatens Their presence through atonement fatwas.

The latest fatwa is not new in the area of Libyan contradictions. A few years ago, the office of the General Authority for Endowments and Islamic Affairs in the city of Zuwara on the border with Tunisia denounced a fatwa issued by the “Supreme Fatwa Committee” of the previous interim government headed by Abdullah Al-Thani in Benghazi, which considered Ibadis “a deviant and misguided sect.” “And that they are “from the inner Kharijites, and it is not permissible to pray behind them,” considering it “an explicit call for sedition, a hidden incitement to fighting, and an excommunication of the people of the country who have lived for centuries as a single Islamic society.”

It seems that the main difference today is what this situation imposes at the border level with Tunisia, and the possibility of “armed conflict” between the Amazigh and the rest of the factions affiliated with the Tripoli government.

Political escalation

The issue can be looked at according to different dimensions related to the Libyan cultural formation, and this matter is considered part of the issues of the cultural fabric, and it gives richness to social life in the event of political stability, but amid the current conflicts it constitutes a crisis that most international initiatives are trying to ignore.

Recognizing the rights of the Amazigh is not just a political measure, but rather part of the social contract that is supposed to be determined by the country’s new constitution. The sensitivity of the issue lies in the ability of the forces that will participate in the upcoming elections to create a balance between these rights and Libyan national unity.

Two basic issues can be considered in this matter:

- The first is that the new Takfir issues are not far from the Libyan political impasse, as it can be read as part of attempts to obstruct any diplomatic effort or attempts to hold a dialogue leading to legislative and presidential elections.

Within this issue, the Amazigh appear as a situation that can be raised or placed within the forefront of the event and made part of the contradiction that prevents consensus. Breaking “national unity” by provoking a sectarian situation cannot be viewed normally, but rather as part of maintaining the current state of division.

The second issue is related to the Ras Jedir crossing Regardless of the differences between the Dbeibeh government and the Amazigh’s in that region, this crossing, in light of the security “dispersion” and the multiplicity of factions’ references, will automatically push the Amazigh issue to the forefront.

The problem does not appear to be the Amazigh demand that their interests be taken into account at the Ras Jedir crossing, but rather the lack of confidence in the security situation in western Libya. The military units affiliated with Tripoli have loyalties that go beyond the government and possess a kind of freedom outside the decisions of the political authority, which increases the fears of the Amazigh in particular. With the emergence of fatwas accusing them of atonement.

All the solutions proposed regarding the Amazigh do not dispel their own fears, or even the fears of the other party, which views calls for cultural rights with suspicion. In light of the current political conflicts, the national dialogue will remain a first step towards a solution if it can be freed from external influences. The Amazigh need a social contract that does not dispel their fears , Not only does it achieve cultural assimilation, but it places them within the line of defense of national sovereignty, and this is not currently available under the conditions set by the Dbeibeh government in the face of dialogue.

Written by Nidal Al-Khedary

Algerian boxer Khelif after winning the gold: This is my dream and I am an Olympic champion today